JEFF MEET REMBRANDT, REMBRANDT MEET JEFF – HE’S A BIG FAN OF YOURS.

Where do you begin to start with Rembrandt ? The first time you saw one, the first time you heard the word? The date of his birth in 1606? So for want of anything that is a neat chronological fit let’s start with yesterday.

The Gagosian gallery in Mayfair is a cool box of architectural purity, relaxed and welcoming – at one with itself like a small museum, it isn’t trying too hard because it doesn’t have to. Whatever comes through those doors (the door is always opened for you whoever you might be) matters nothing to them. Their prestige comes from elsewhere they can afford to appear generous.

There’s an artists’ self portrait exhibition. With the power of a multinational art juggernaut Gagosian has bought Kenwood House’s Rembrandt – temporarily. In my mind I’m always comparing Rembrandt with the contemporary art that is around me – now I can do this in reality. It’s probably impossible to compare something you love with something you hate and give either side a fair hearing. So I won’t bother trying, at the end of the day we are largely prisoners of our own tastes and our own experiences. What I am here for is Rembrandt versus Koons. Something like John Connor versus the Terminator, all that is human against all that is not. The fact that this is set out within the confines of the Gagosian Empire isn’t lost on me either. The comparison is made all the easier as the Koons in question is a sort of Rembrandt self portrait. The original Rembrandt is arguably his finest self portrait completed during the final years of his life in the knowledge that it had all come to nothing but yet without that failure Rembrandt could not have fully become himself – as life transformed him he transformed art. Compared to that I honestly don’t know what Koons or Gagosian have to offer.

As the exhibition develops there are a couple of Glen Browns, another artist playing on the old master contemporary master theme, as lively as the works might appear they are highly controlled. Calculated and calculating. Finding the Jeff Koons Rembrandt sharing many of these characteristics its outcome however is not a unique piece in the same way as Brown’s; every detail of the Rembrandt (the original is in the Thyssen Collection in Madrid) has been painstakingly rendered but to a larger scale without any of the original’s physical paint handling resulting in something that looks like a poster – distinctly there but simultaneously not there. The work has no presence and no psychological impact. The connection with Rembrandt is almost by chance, completely arbitrary as if back at his manufacturing base Koons has flicked through a Rembrandt book and haphazardly stopped at some page or other. His labourers have then made what we now see, they’re clearly highly skilled but this skill is utterly devoid of meaning other than to fulfill the terms of their employment – the intrinsic humanity of the original was on no one’s radar. Regardless of intent (Koons in his promotional interviews talks of the spectator’s enjoyment of engaging with masterpieces and how the works he has chosen are in his DNA as an artist) the work can only serve to highlight the differences between his artwork and the original from which it sprang. There is though something else. If you follow Koons’ exhibitions you will know that these facsimiles aren’t stand alone objects. Regardless of which masterpiece has been ‘copied’ they all come with a shiny blue ball screwed onto a small shelf coming from the centre bottom of the image. Koons himself makes a great deal of fuss about how perfect these ‘gazing balls’ have to be, their surface is meant to beguile us as we dumbly delight in seeing ourselves in the place that we know ourselves to already be. This is infantalised distraction – a stylised image of reality that reveals nothing, withholds nothing – an elaborate emptiness that causes the image behind it to be utterly diminished. The ball is more than likely Koons waging war against what he professes to love. Whatever the painting, however great you imagine it to be my perfect blue grenade will shatter it, will render it invisible as you are inextricably pulled towards self regard. Unsurprisingly the Koons is hung nowhere near the actual Rembrandt. The real battle is avoided.

The first Rembrandt that caught my attention back in 1983 wasn’t one although today some people think it might be. To my mind it isn’t but Rembrandt is undoubtedly in there. A pupil has probably made this under guidance; the master might have touched it or might not have done. The one thing that drew me in, dared me to rethink what I thought I knew about painting was the audaciously impasted arm and hand. There is a dangerous excitement about the prospect of ruining a finely crafted picture with such overtly daredevil behaviour. As I’ve looked at this arm over the years it has struck me as less and less successful and unRembrandt like in the way that this particular gamble has not paid off in spectacular fashion as it does in say the portrait of Jan Six or Woman Bathing in a Stream. Rembrandt backs himself to within that single moment spontaneously conjure something that is both expressively alive yet also specifically defined. The painting I’m looking at gambles but falls short. In essence it is not Rembrandt enough. Back then the idea of using spontaneity to create a sense of reality was so utterly alien – I was totally wrapped up in notions of diligence and slog as I tried to work out how to be a serious artist. This painting also had elements that were entirely new to me, abstraction and texture within representation. The pretext for these experiments were the man’s garments some sort of heavy luxurious textile the sort of thing one might imagine biblical characters to wear if it wasn’t for the regional climate. The textures themselves create mood, make clandestine appeals to the subconscious creating a sense of experience involving us further without our quite knowing it. Rembrandt’s use of the physical properties of paint was both his making and undoing, when the fashion for smoother finishes rolled in he became rougher and rougher; he’d become addicted to experiment.

I always drew pretty well but as you might expect there was a gap between what I wanted and what I could achieve but I worked hard to close it so that results were at the very least acceptable. I had got to a point where I knew how to draw but I also knew that something was missing – something that facility and practice could not deliver. I visit a lot of exhibitions, I always have done. Almost twenty years ago I went to an exhibition of Rembrandt’s prints at the British Museum. To date it is the only exhibition in which I’ve hit my head on the display glass as I’ve moved in for a closer look and become totally unaware of its presence. In addition to the prints themselves the exhibition also displayed a number of Rembrandt’s plates which often he worked and reworked not simply to develop his image but to sometimes entirely transform it. The texture within many of his prints were as alluring as his painted surfaces a kind of dense cloak of black that still offered the sense that one could still somehow see through them. This was how he demanded close attention, not by presenting a subject but by wilfully obscuring it knowing that our curiosity would drive us further. His prints also captured a range of physical activities, in places metal was gauged directly into like some form of aggressive expressionism, in other places an etched delicacy prevailed. There wasn’t one way of making these things – choices were instinctively orchestrated in places he opted for harmony, in others he invited chaos.

It occurred to me that I might extend the processes within my own drawing treating my paper in ways that Rembrandt treated his plates. My drawings could become things in their own right as much as say preparation or studies for paintings; it was the start of a journey where I was more willing to disrupt myself, change my mind entirely and create a far greater sense of mood within a drawing. I was looking to create a sense of life not simply within the drawing but within the imagination of the person who might then look at it.

I can’t imagine Jeff Koons engaging with Rembrandt at all. I can’t imagine Jeff Koons engaging with anything. At the end of the Gagosian exhibition Kenwood Rembrandt is there, impoverished but defiant – a flea bitten loser and at the very same time the king of all alchemists turning coloured dirt into the essence of our humanity. He stands there holding his tools, some sticks or a wand ? – we can’t actually see, instead we sense what the paint might become without the need to be shown. In that single part of the picture we can understand what Rembrandt is an artist and what Koons is not. This painting puts all others to the sword. Rembrandt stares out through time into the exhibition into an artworld that has mutated for the most part into an entertainment industry. He stares unflinchingly, his lips are motionless as they always have been but he still speaks.

Paul Brandford April 2019

STILL LIFE

There had been boastfully enthusiastic talk of going to Paris between a few of my friends from Foundation, the sort of thing aspiring artists were supposed to do like a gang of teenage Tony Hancocks out to discover the true meaning of art. It didn’t happen (I was disappointed yet unsurprised) but then again neither did my smooth transition from Foundation student to undergraduate. As it transpired neither Camberwell or Newcastle Poly were suitably impressed by a year’s worth of workmanlike nudes and still life. Camberwell, my tutors had pushed me in their direction as the best place to learn, gave me some consideration but Newcastle burdened by the weight of applications and the knowledge that this round of candidates had desired somewhere other than here gave me almost ten minutes at the end of a hectic day during which they had lost the will to fabricate any pretense of interest. So there I was not in Paris or London or Newcastle but at home in Welwyn Garden City with parents whose belief in their son’s inability to make adult decisions was now fully vindicated. Much to their disgust I wasn’t looking for a job, I wasn’t looking for a new career path I was looking to spend more time alone in my bedroom painting pictures.

Despite not being in any mood to reward failure I booked a three night stay in Paris exhausting what little savings I had. Reading this some thirty five years after the event the purpose of my trip will strike you as blindingly obvious, it turned out however that my parents had fully convinced themselves that I was embarking upon some sort of sexual liaison with someone (probably male) as yet unknown to them. My interest in art was entirely preposterous to them; no good would ever come of it but at the end of the day it was none of their business.

I was in Paris for what I knew I liked plus whatever else I might encounter by chance. The Louvre’s grand galleries were home to vast pictures heroic in scale but often lifelessly bland, moral instruction from ancient Rome were about as inspiring as my dad’s insincere career advice. Within the collection there was also a number of small paintings; small in scale but yet endlessly engaging in a way that the neoclassical warriors and philosophers were not.

Back then the National Gallery in London had a Chardin still life on show, oysters on a dish with a bottle and a knife teetering upon a ledge. You can’t see it today. It was on loan from the British Rail Pension Fund, they cashed it in at auction. It was a more than decent painting but the Chardins in the Louvre somehow came to life in a way that the London example could not. Light moved across the surfaces of a number of objects revealing their textures, their imperfections, their reality. Everyday forms are rendered extraordinary as shadow, reflection and colour move from ambiguity towards an intense realisation creating something more seemingly epic than those grandiose depictions of heroism and loss. Chardin transformed paint. I could see that. But I couldn’t see how he did so despite endless looking.

Over that past year I had been taught to paint with oils, clean palette, premixed colours draw by placing colours next to one another. Redraw when necessary – by which they meant often. Essentially we were an army of third hand Cezannes created to slot into Camberwell, Wimbledon or Norwich; Chardin was from another planet as far as technique was concerned, like Vermeer in that respect his is an art drawn from everyday experience which is utterly compelling yet at the same time inaccessibly remote.

The Jeu de Paume and Orangery were still functioning as offshoots to The Louvre; the Musee D’Orsay had not yet opened to become the focal point for French Impressionism. In 1984 I had yet to visit a blockbuster exhibition (other than the British Museum’s Tutankhamen as a seven year old). Trying to navigate a sea of fractious people to fleetingly look at a picture from something other than an acute angle was something I would become adept at but at this point it was overwhelmingly difficult. Punters had paid their money and expected to see what they’d come for only the Jeu de Paume wasn’t expansive in the way that museums are now. As an environment it was far from conducive but it was also late July, the height of the tourist season.

Manet, Monet, Degas and Cezanne were all familiar to me but going to a city – their city to seek them out seemed important. I didn’t speak French to any functional extent but I didn’t much care. I wasn’t there to talk with people I was there to look at paintings and forget about where I had come from. Cezanne was oddly discordant, the paintings don’t offer a harmonious balance as much as pockets of imbalance that would somehow reconcile themselves or keep the eye on the move to such an extent that one loses awareness of what other – more obvious pictures demand us to believe. His fruit was on the verge of falling from mountain ranges of drapery, the stability of Chardin’s stone ledges was something he no longer required. These pictures had become surrogate landscapes with their own internal force fields. I came home wanting to be the kind of artist that I felt Cezanne to be. Rigorous yet dramatic; modestly wrestling with his own genius and the demands that it made upon him. The only difference was that I had no genius to speak of and no real concept of how to paint my own paintings.

Back in my bedroom I was keen to bring all of my DIY Cezanne ingredients together; fruit was easily available as were my parents’ pots, jugs and prized lladro ceramics. Bizarrely I also had access to the sort of fabrics that Cezanne favoured. Of the three children in our family I had ended up with the largest bedroom – it was also deemed to be the coldest as it was situated directly above the house’s built in garage. The three of us initially shared it when we moved in, my sister then was swiftly relocated to the sunniest, airiest of the bedrooms designated for our use. My younger brother opted for the smallest room insisting that it should be painted a very warm yellow – almost a sickly form of orange. He and I were given blue nylon carpet; I also retained guardianship by default of a relic of our past life in Luton – my parents’ old wardrobe complete with all the clothes they didn’t require on a day to day basis and a narrow oval mirror which I used for self portraits. It had been put there on our arrival in 1970 and was destined to remain for a further twenty years. Other items that had made it across from Luton were the curtains that furnished the room, a thick textured material with a repeating floral pattern. I’d estimate that these were from the early 1960s – the colouration was so austere that any sense of gaiety that the flowers might have possessed was easily neutralised. For years I had disliked these curtains as a symbol of my insignificance within the familial set up, their dense strings of robust blooms almost like bars on my suburban jail cell. Now however they finally had a purpose, with their help I could be less like Paul Brandford and more like Paul Cezanne.

My parents were not impressed in the slightest; my sister was at university becoming the epitome of social mobility as I was languishing at home with no discernible prospects, an embarrassment to be barely tolerated but rarely confronted. Regular visits to the Foundation College kept me afloat, they became my parent.

It soon became time to seek an undergraduate placement once again. Newcastle and Camberwell would not be given the opportunity to reject me twice so I made other choices. One of my friends who had been in on the Paris plan had, surprisingly in my opinion, also been rejected by Camberwell last time out had gone on to find a place in an art school beyond the realm of that particular system. As an insurance policy it seemed ideal so I found myself applying with no particular thoughts of success or failure in mind to The Royal Academy Schools.

Their admissions procedure to the undergraduate course felt somewhat archaic, to the point that a character from Great Expectations might do this and the reader wouldn’t raise an eyebrow. The course itself however was pretty new and (not that I was made aware of this) about to be dissolved. Initially a portfolio of drawings was delivered for their leisurely consideration. The Schools had studios running off a windowless corridor full of plaster casts of antique sculpture; portfolios were delivered and stacked here then hopefuls awaited news. From one hundred or so applicants twenty were invited for interview. Approximately ten places would be offered. Knowing that they liked the drawings I felt pretty confident that I could be in the stronger half of the interviewees. If not the atrophy of Welwyn Garden City could be back on the menu – that in itself was a keen motivator.

In September 1985 I moved out of my bedroom to an equally sized room in Balham. The largish terraced house was owned by a Hong Kong Chinese nurse who lived elsewhere and rented out each room separately mostly to Chinese students studying in London. The house was also home to a huge and untreated cockroach infestation. The Royal Academy offered no extended student services but then again no one was demanding any. Students were scattered across London, largely living in poor conditions dreaming of becoming successful artists. The Schools themselves were looking for something with a little more glamour. They were in the process of reinventing themselves as a forward looking post graduate only art school to rival the likes of the Royal College, bringing in new leadership, new tutors and new priorities. The last thing they needed was a student in love with the past turning out endless still lifes. Like a tiny majority of the students there I had taken up using a palette knife so that my pictures had a distinct look of being constructed in a way that was analytical rather than emotional – the colour is mixed, the colour is placed – clean, methodical and unyielding quite the reverse of the Cezanne pictures made with the same utensil. By pure chance these were on show in a dedicated exhibition whilst I was a student – a very different Cezanne to the one that I was trying to imitate.

One of the new tutors without any hint of emotion or involvement informed me that the still lifes I had earnestly laboured over were in fact hackneyed pastiches. She was right of course but offered no advice, no way forward towards the kind of painting which might gain her approval. In another part of London the Young British Artists were developing their visions and coming together as a new force on the cultural landscape – I on the other hand was adjusting and readjusting the tonality of small painted bottles. I wasn’t the future of art, I wasn’t going anywhere or influencing anyone but I wasn’t going to stop, I moved north of the river to about five minutes walk away from where I’m typing this. I continued with the still lifes for a further four years becoming familiar enough or bored enough to take greater liberties with a picture’s outcome and actually enjoy doing so. I dropped the palette knife and picked up brushes again, I also stopped thinking that things had to be done properly to some sort of invisible standard. This wasn’t anything to do with the outcome of the work but more to do with how an artist might operate. I didn’t need to paint on linen canvas, neither did I need a mahogany palette which I had purchased locally in Wewyn Garden City to demonstrate my seriousness. I never once owned a smock or a beret but quite naively my early sense of what an artist actually was very much bound up in that kind of caricature.

The luxury, which I had become so entirely used to, of spending my time scrutinising small objects and then painting something was soon to abruptly end. Still life is largely about the artist being in total control, that particular world is created and to an extent ordered, anything beyond that is consciously blanked out. The moment arrived when I no longer had that time or the capacity to control my surroundings. Overnight that activity and all that went with it became redundant. My son arrived and I became a finger painter.

Paul Brandford November 2018

A GIACOMETTI PORTRAIT

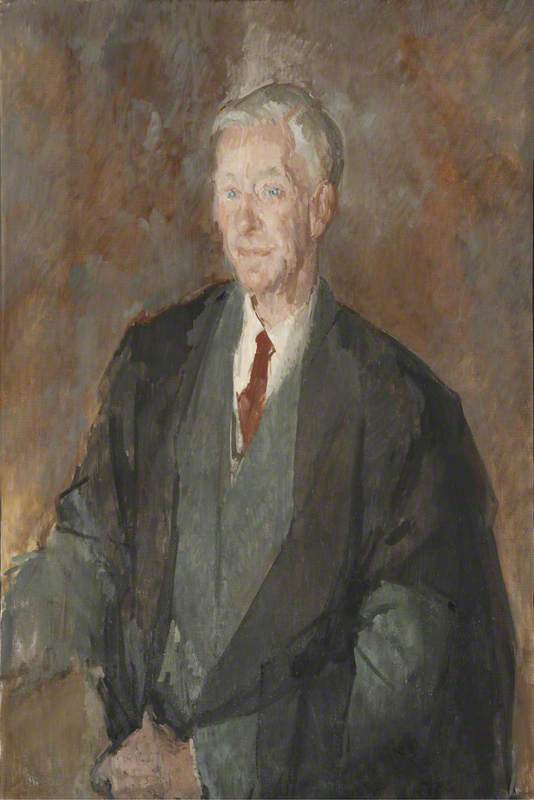

Of all the cultural hotspots that Britain had to offer Herts College of Art and Design opted to bus those who were willing to Norwich. The next step – being selected by the art college who could somehow imagine sufficient potential to offer up one of their valuable places was at the back of everyone’s mind. Hundreds of foundation kids were being pumped out, kids who were arty, kids who made art and kids who didn’t want a job – art schools could be as picky as they wished. Norwich School of Art and Design was held in high regard by my tutors, one might be taught how to paint properly by the stolid yeomen of figurative painting who ran the place. At Norwich Art School was an exhibition by Peter Greenham a well respected artist in the British tradition slowly producing carefully delicate portraits and landscapes. The people in his pictures always seemed in danger of melting away or looked as if they were in a somewhat smoky room where nothing was clearly visible. His choices were provisional almost tentative and somewhat twee. These tiny flickering decisions would build up and become amalgamated into something that felt like a blurry image of say a character from Downton Abbey or Agatha Christie. They certainly didn’t feel that contemporary to an eighteen year old only just finding his way into hair, clothes and music. At that time I made no connection between these and what I was about to see at the University of East Anglia.

Peter Greenham; John Traill Christie, Principal (1949-1967); Jesus College, University of Oxford

John Wannacott – The Life Room, Norwich School of Art 1977 – 1980

Some fifteen years later when my son was of primary school age I bought him a small range of books that I thought he might like to have read to him, they were books from my childhood – not from my home but from my school; The Iron Man, Stig of the Dump and Alan Garner’s Weirdstone of Brisingarmen. The Weirdstone was a book that one the one hand terrified me as a child but on the other hand was relentlessly gripping; I wanted my young son to have a similar experience. I’m not sure as to whether we even finished it however – he found the cover of the book so disturbing that he wouldn’t even have it in his room in the vicinity of bedtime. The cover depicted an elongated hooded figure in a forest clearing – his face unseen or in fact unseeable through its absence. My son was in general pretty fearless, well known for his love of daredevil antics but he did not like what this book cover did to his imagination, there was only one other incidence where he felt that same sense of dread. I owned a book by David Sylvester called Looking at Giacometti – to illustrate it he used photographs taken in the late 1940’s by Patricia Matisse of Giacometti’s sculptures in the twilight setting of his dingy studio. Patricia was the wife of Pierre – one of Henri Matisse’s sons who had set up an art gallery in New York and was keen to expose these strange works to a wealthy American audience.

These images initially grainy and ambiguous yielded their contents as strange forms emerged into the light, they bore no resemblance to anything the Matisses had ever previously encountered but to my son’s eyes they were the realm of the undead made real through photography – threateningly unclear yet hinting at same dark magic that Garner’s book touched upon. My son did not know this but Giacometti’s lifelong fascination with ancient art forms was at the heart of almost every object he ever made. Life, death and afterlife stalked the imagination of both artist and child.

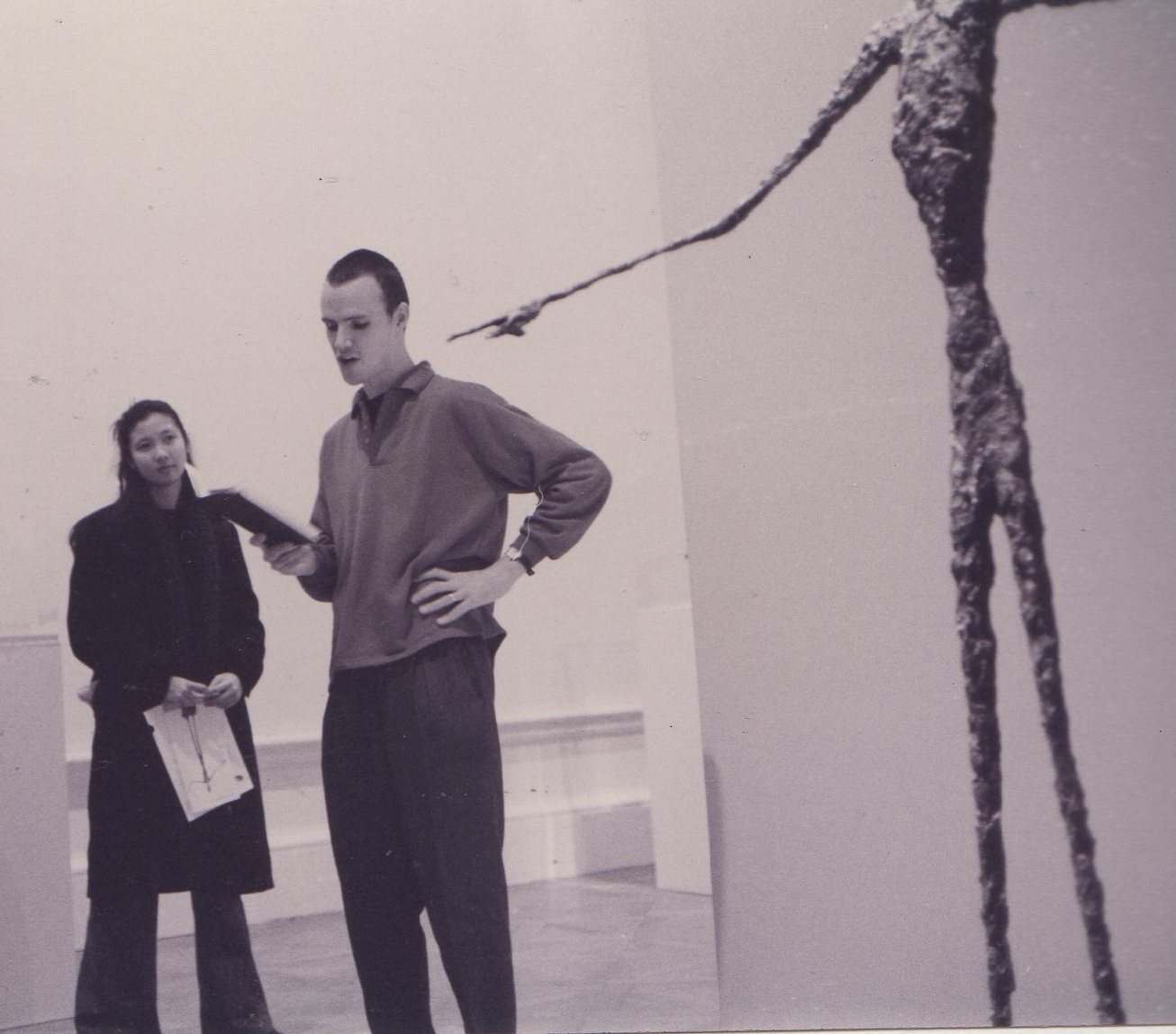

The Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, part of the UEA, a split level open plan aircraft hanger of sorts set in the grounds of the university housing ethnographic artifacts, a good selection of Francis Bacon paintings from the 1950’s and an exhibition of Giacometti’s later works. Here was one of the few places that combined contemporary art with a historical collection, something I’d never previously encountered. The notion of labels, categories and boundaries that judgments about art seemed to depend upon in my mind back then were effortless sidestepped by this form of presentation, something that back then wasn’t entirely reassuring to someone keen to label themselves as this or that sort of painter and belong. Giacometti too defied simple definition with a mixture of drawing painting and sculpture all of which seemed to be of equal importance to him. These disciplines were interchangeable facets of the same curious imperative; Giacometti’s unending desire to render a subject as he experienced it was contradicted by works made purely from memory bearing little resemblance to everyday reality. His working routine was beyond habit and something more akin to ritual where works were created and destroyed many times over in pursuit of an unattainable goal. The sculpture struck me as odd in a way that the paintings and drawings did not. As much as they were representations of people they were clearly independent objects with their own sense of self. They were charged with a kind of energy that came through hundreds of cuts, gouges and scrapings. The things we were looking at had somehow survived the ordeal of its birth – but only just.

The paintings and drawings would offer more direct clues as to how this manifested itself as I had never actually attempted to make a meaningful sculpture at that point. As with Peter Greenham, Giacometti was keen to deliver the sense of form and the sense of the surrounding space together as this is how we perceive. Our brain may separate the two but that is a conceptual act rather than something we directly experience. This simple idea was the purpose of our trip to Norwich, punting up the art school was a fortuitous bonus. In later years as a proper art student days were spent on drawings where the extent of forms (often pots and bowls and bottles) were meditated upon. Does the form expand into space as one creates its contour or does the distance of that form from your fixed point of view mean that it diminishes into the distance? Edges of things were drawn and redrawn as the optimum position for any boundary was sought after without preconception. I imagined myself as a miniature Giacometti searching for something truthful something that only the determined could possibly stumble upon as if by chance. That particular sense of doubt within figurative representation was seen back then as a noble thing, a modest thing, a heroic thing – we were encouraged to be that kind of hero. Figurative Exhibitions at the time were given titles conveying some sort of moral overtone; The Hardwon Image, The Pursuit of the Real and even The Proper Study. All of this can somehow be traced back to Giacometti’s grotty little studio – the epicentre of a belief (or disbelief) system.

Finding myself based in the West End of London with a decent amount of grant money a mania for collecting art books soon took hold and developed. Possessing what one desired ( if only in book form) created a sense of achievement somehow. People might own a nice house or a nice car but I own a slim volume on Morandi’s flower paintings with an essay that touches upon the bombing of Bologna railway station. Another of the books I purchased back then was James Lord’s biography of Giacometti, it was heavily criticised for its supposedly gossipy tone and lack of serious appreciation by those in the art world who had once known him personally. As I read it however it placed his artwork within the influence of the ominous alpine landscape of his childhood, the ongoing tension between him and his artist father and the self imposed exile from a group within which he was finding early renown. The life of an artist and the work which that life generated are rarely as emphatically intertwined as they are in the example of Alberto Giacometti.

Artists are in general not too keen on their working processes being recorded but Giacometti in the act of working has been something that many photographers did indeed capture; these images have become representative of a certain view of artistic activity. The artist works alone in a small studio which verges on squalor or chaos. This environment is purely the invention of that individual. Hour after hour is spent in pursuit of a vision that is somehow at odds with the rest of the world. It’s unusual that spectators would be allowed to intrude in such a way but I believe for all of his remarks about disinterest in fame and fortune Giacometti was keenly aware of their publicity value. So what was he doing in there? Something on the one hand practically pointless and yet on the other expressing something at the very centre of our shared humanity. It is no coincidence that Giacometti through this pursuit is strongly connected to existentialism. Although he knew that movement’s outstanding authors personally and cultivated relationships that produced catalogue essays and other published material (a more cynical writer might describe this as a branding exercise) it is an oversimplification to view his work entirely through that particular lens.

This activity, existing in its own time span operating to its own rhythm instinctively fiddling, scraping and cutting inert material, either clay – intrinsically dirt and water, or a rapidly drying plaster in an attempt to cajole it into being more than just itself. To somehow become all of us through some willed act of transformation. Anyone sitting for a painting or sculpture made from direct observation would be required to stare back at the artist for their life’s worth. He like the ancient cultures believed that the life force was in the gaze. A head and by extension the whole person is alive because it can look, because it can see. Everything in Giacometti’s later work stems from that.

In 1996 I did a set of talks on a Giacometti exhibition in London for school groups. As it was a retrospective it began with a number of post impressionist influenced paintings – his father was one of Switzerland’s leading exponents of this approach, Annetta his mother was somewhat perplexed and disgusted that their son through his shockingly ugly works (in her eyes) became world renowned leaving Giacometti senior very much overshadowed. Giacometti’s surrealist phase full of disagreeable objects, unplayable games culminated with ‘Woman With Her Throat Cut’ part mantis, part Picasso like some desiccated plant or skeleton laid out before us in orgasmic convulsion or agonised misery in front of our eyes. The trachea with its brutal gash and its gaping mouth violently gasping for air seem to crystallise a misogyny which was prominent in male surrealist circles. Once this avenue had revealed itself in 1935 as a cul de sac Giacometti was banished as a heretic from Surrealist circles turning his attention instead to the human head and then the figure as something which might unite his love of the past with the experience of the present becoming the Giacometti who was fundamental to British figuration for some thirty years or so.

Alberto Giacometti, Woman With Her Throat Cut 1932

Both the National Portrait Gallery and Tate Modern have recently put on Giacometti exhibitions; the chance to revisit his work is a pleasure that cannot be replicated by books despite the fact that his works are strikingly photogenic. In addition to the paintings, the drawings and the legion of standing women he made two large versions of a walking man. I have vague memories of seeing one in Norwich, the Tate Modern show made a distinct point of ending with one as a dramatic statement of his unceasing desire to progress towards the realisation of his vision.

The walking man has little to do with observation – he is a symbol, a talisman. His thinness isn’t anything special when taken as part of Giacometti’s output, as much as he has been constructed – built up in layers of scrim and plaster he has been pared down again and again leaving behind only what is essential. As we look we might begin to dream that he is actually walking; he carries nothing that is surplus to that requirement. No clothing, no possessions, nothing that characterises him or defines him in terms of race, class or profession. He is like none of us and like all of us simultaneously. He appears to be well balanced and would travel fluidly, efficiently, relentlessly until the journey was over. He travels towards his destination, our destination, where we will all at some point find ourselves. He journeys willingly and with a determination to complete his task without pause, without distraction.

As much as he is a representation of or a prompt for these kinds of thoughts he is an object and a peculiar one at that. He doesn’t look like us; he looks partly comical, even ridiculous. He is almost the height of a heroic sculpture but not at all physically imposing in terms of portentous bulk. Close up he is not so dissimilar to lichen covered timber or fossilised remains. That sense of vitality that his smaller sculptures crackle with is not quite present almost as if this is a step too far. But here he is and here we are. Giacometti had this urge to create on the larger scale even though he may well have known it was near impossible. (If you didn’t know he was always complaining that everything he was trying to achieve – even the smallest part of it was in fact impossible). Misplaced ambition often creates within a body of work something revealing, perhaps explicitly through its weaknesses, more of humanity than what might be expressed by works made more fluently, routinely. I sense that the walking man as an aesthetic object is not such a triumph but the walking man as a container for the ideas that we had about ourselves in the aftermath of World War Two has a power that is undeniable.

Twenty two years ago towards the end of one Giacometti talk I was looking at a particularly wide eyed portrait of his wife Annette ( a good deal is often read into the fact that his wife’s name is almost the same as his mother’s)- someone who was at the very centre of his enterprise posing for countless sculptures, paintings and drawings. Describing how sitters were instructed to stare back attentively to a bunch of rough and ready school kids from Manchester on their first visit to a London gallery I replicated the strangeness of that interaction with help from one of the students. From across the gallery someone who clearly felt that Giacometti should not be discussed in such a manner shouted at me almost despairingly ‘I am a lecturer. Just tell them that they are beautiful’.

Back in Norwich my teenage self could not find Giacometti’s particularly beautiful just somewhat odd. The fracture between his created reality and my limited understanding of what art could achieve was only bridged by that much maligned James Lord biography. Lord also published other books on Giacometti – a large book on his drawings, the only thing that I have ever overcome my embarrassment to actually haggle over the price for and A Giacometti Portrait, a modest book in diary form capturing the experience of sitting for a painting over eighteen days in 1964. Some fifty years two later I found myself in row one, seat seven – the front corner (an awkward viewpoint obtained with the last available ticket) of a twenty eight seat cinema of comparable size to Giacometti’s studio on the Rue Hippolyte Maindron. Geoffrey Rush created a Giacometti part genius, part clown full of anxious restlessness trapped within and liberated by a world of his own making for a film version of that particular book. The flawed beauty of this man in this place transported me far beyond my actual surroundings.

Paul Brandford October 2018

YOUR WAITRESS TODAY IS MANET

The Visit

It turned out that I wasn’t university material despite my desire to do what was expected of me. The local art college had however offered me a place requiring only functional rather than spectacular grades to secure it for the following September. Immediately I stopped working towards my exams, for the previous three and a half years I had been plugged into a belief system which all of a sudden became irrelevant. There were a lot of things that I just didn’t need any more, there were a lot of other things that I needed to understand and quickly but as it turned out I would prove a ludicrously slow learner.

They sent me a list- a list of places to visit which were largely art galleries and museums in central London, up until then Finsbury Park and the roads surrounding Highbury stadium was the only part of London I knew with any amount of intimacy. Historical collections featured prominently within the list, back then it was my firm belief that historical art would always be superior to (let’s call it) modern art so I made the decision to visit these places first.I began with the National Gallery, at the age of eighteen I had committed my immediate future to becoming a practicing painter but had yet to set foot inside the place. To my knowledge no one that I knew had ever done so either.

There is a lot of discussion in the gallery and museum education sector about accessibility, a lot of talk about newcomers being put off by porticoes and grand entrances, how people might feel intimidated by or inferior to something which in reality belonged partly to them. How was one expected to behave? I knew I wouldn’t be touching anything but there was and still often is, an ongoing sense, that visitors to art venues should be quietly reverential as if in some kind of cathedral to culture. As it turned out, more through lack of directional sense than anything conscious I entered via the back entrance – an afterthought looking like the entrance to a department store in a satellite town, modestly functional and in no way off putting. It gave no hint as to what was beyond.

The first thing to strike me was the atmosphere of the place, luxuriant yet at the same time seriously dedicated to displaying works at their best – precisely as my eighteen year old self would have imagined it; silk hung walls, elaborate frames and opulent paintings. This was the exact opposite of how I had experienced the Tate Gallery two years’ previously which had been oppressively white and visually arid quarter filled with objects which at that point in time I had no means of understanding – almost a futuristic parody of what I then believed in. Instinctively I was much more at home here, a proper environment for proper art. The works that attracted my attention back then still attract my attention thirty five years later, as much as they might be static objects they are designed to provoke reaction – personal reaction; internal and unspoken. Over time as you pass by or peer into these things on a semi regular basis they become like household mirrors in which one might accidentally glimpse oneself in an unexpected way.

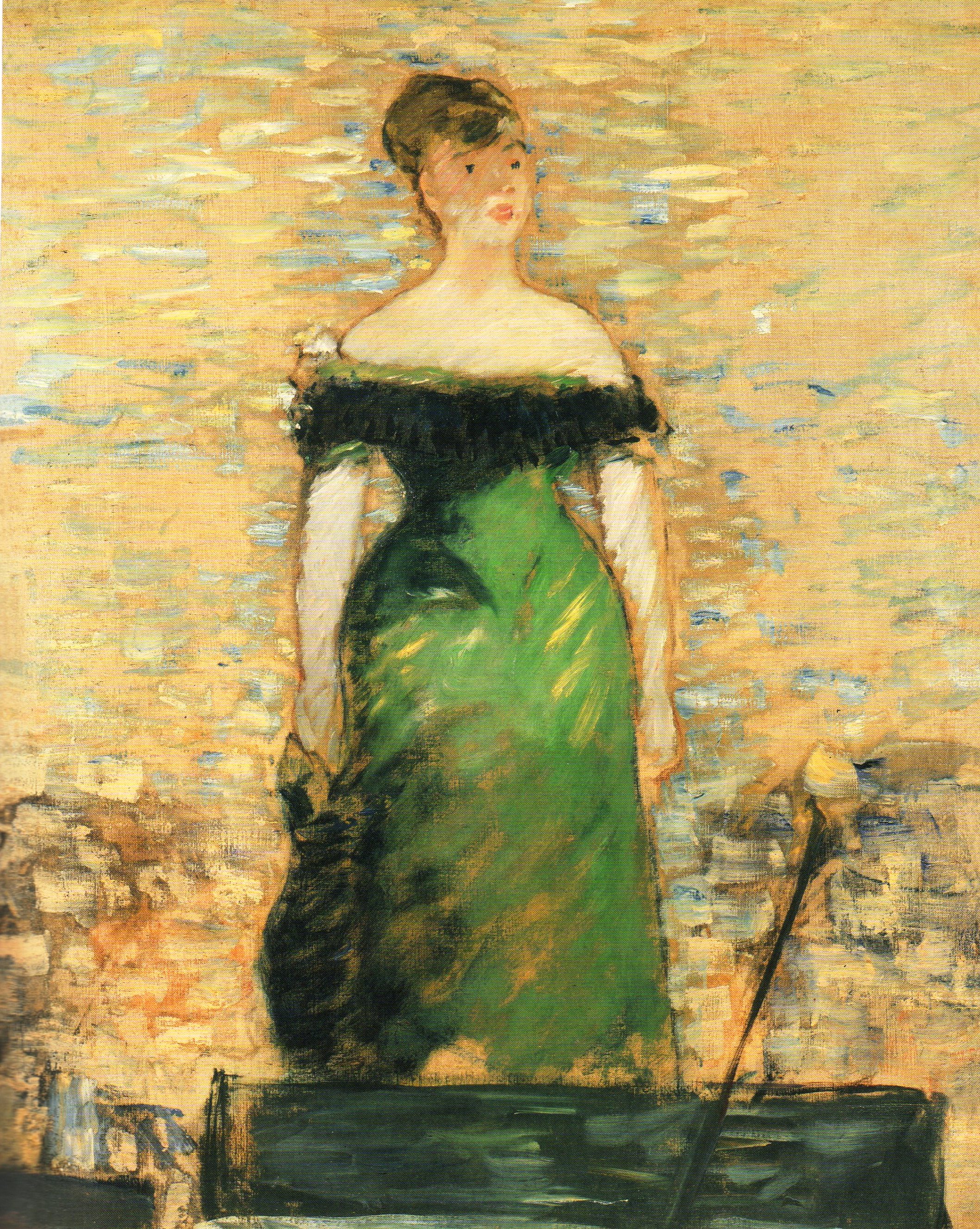

Back then I might have been capable of naming five artists more or less, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Picasso, David Hockney, Dali, maybe Monet but that was more or less it. Manet certainly wasn’t one of them at that point I knew nothing about his paintings, the Salon rejections, the public humiliations, the unrecognised offspring or the amputated leg. Initially I just looked at a painting which caught my attention.

Manet

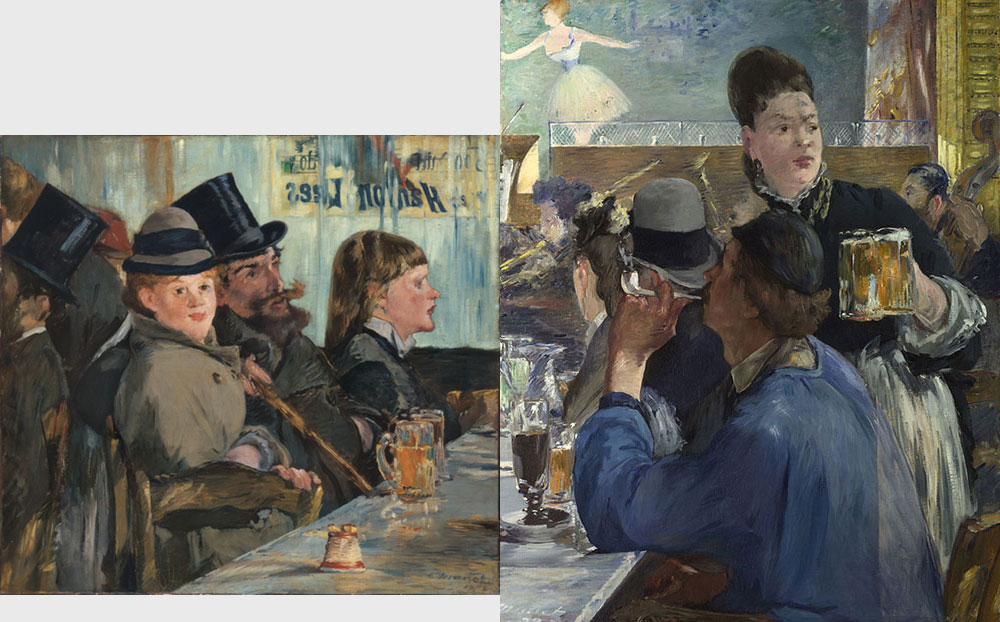

At the very beginning though the thing that confounded me was how certain parts of the picture felt utterly convincing – the hat, her head, the bustle of the place yet others were so willfully awkward in their making. Spaces were compressed, fingers were bodged and anatomy was skewed. As much as it was a picture of a place within which so much seemed to be happening it was a puzzle which almost refused to add up, different areas having their own properties and functions beyond their servitude to a sense of wholeness. As events happen around us we cannot see everything at once- we are distracted as information catches our eye by way of colour, contrast or movement. The drinks shimmer as light catches them inside their glasses; the bassist’s determined look of concentration, the poise of the dancer caught mid movement, the hand lurking beneath the table. The protagonists seem motionless while their world revolves around them. At this still centre is the waitress, the smoker and the hat. The hat and the waitress’s head show signs of being endlessly redrawn, endlessly repainted until information as if by chance lands in the right places. Her face, full of distracted movement remains subordinate to the physical substance of her head, she flicks a glance towards something unseen by us as we study her predicament. By contrast the smoker is present but is much less of a presence, his attention has also wandered – disturbed not by something external but lost somewhere within himself, within his own thoughts as he smokes and as he does so he almost begins to dissolve. His head, his cap, his hair are full of a flickering transience but his arm- that has another purpose. As his shoulder tilts into the picture his arm begins to follow suit but before it can fully do so it stops and flattens out to form a column that pushes us upwards past that disconcerting join between the hat and the female customer gazing inwards and onward towards the performer in the corner. It is clearly a pictorial device but one I didn’t notice for many years. Manet gives some hint as to where we might expect to naturally discover the smoker’s elbow but then ‘squares up’ the join changing tone to dramatise the table and its contents thus disguising his motive. That we don’t stop to question this is down to Manet’s powers of persuasion

Manet was in the habit of asking close friends to pose for his pictures, he had used professional models at one point but that was largely behind him by the late 1870s. The waitress herself was neither of these she was in fact a working waitress from the Café – Concert de Reichshoffen. Cafes such as these were transforming the social life of Paris as strict social divisions became blurred in search of a decent night out. Under Napoleon III cafes had been spied upon for signs of dissent or unrest, the singing of songs – any song was prohibited – once this had been relaxed the café concert scene expanded rapidly. Our waitress posed for three paintings in total doing much the same kind of thing in the studio as she would have done on the job. Manet wasn’t an impressionist at heart – despite a number of plein air paintings he was by and large a studio based artist fabricating a sense of reality using pencil sketches made on location, memory and painterly invention. She attended the studio along with her boyfriend/protector who played the smoker, artists were held to be morally questionable and as such were not to be left alone with young ladies from any background. That Manet struggled greatly in painting her suggests that this was his first attempt, the subsequent two pictures seem comparatively carefree in their handling. The source of this frustration however went beyond an inability to capture his waitress. This painting has a history, as all paintings do – histories of exhibitions and ownership but this one has a distinctly different kind of pedigree.

A strip of canvas has been added, the painter didn’t go to great lengths to camouflage the join. It turns out that the two pieces of fabric haven’t even been sewn together but instead they’ve been lined- paper glued and ironed onto the back of the entire picture to support the join. In the top left where the image is thickly painted (the simplest part of the painting one might imagine) an area has been gauged out (again something that took me a number of years to notice) I then would imagine an angry Manet taking up a small palette knife and scraping out this area in utter frustration at his lack of progress but much more likely it is a botch job on the lining process with the iron accidentally causing damage to vulnerable paint. The thickness of this area indicates that Manet has something to hide. Originally this was part of a much larger painting. In the centre towards the top a singer standing, performing to two banks of café goers either side of the marble topped table. Ambiguously sketchy she may well have been but she was undoubtedly central to the meaning of the picture – the reason for people to be there. The star of the show became the major victim of Manet’s change of direction along with the ambition within the original concept. It always struck me as odd as to why the unseen man had kept his large hat on inside the premises – Manet’s preoccupation with that large bowler hat becomes much clearer when viewing the other half of the original design. In this portion two men are wearing top hats probably demonstrating social rank and a young woman – the only person looking directly at us, wears a casually feminine variant of the hat in our portion. This mingling of the strata was new, cafes with waitresses were new and how these were represented in paint was new.

Manet himself had perfected a Parisian working class accent much to the amusement of his friends; his paintings however brutally factual about the alienating mundanity of ordinary lives and of ordinary life were not condescending or mocking for the sake of voyeuristic entertainment or class tourism. He saw deeper than that. The division of his large painting did not result in two smaller entirely successful paintings – both have awkwardness about them. Within each many parts are stunningly painted in ways that no other artist could pull off – both fragments indicate that there is something performative in the way that Manet paints; there is a tension between his visual language and the image that it creates. The pleasure in instinctively making with brush and paint – playing God, the picture’s subject is (as much as it is a café scene) the delivery of that image, how it might be formed to the extent that it lives and breathes without laborious overkill. The sensation without the tedium of its conveyance.

His later impressionistic works are often held to be less intense, less daring and less profoundly revolutionary than his earlier, Spanish influenced works but they directly embrace life as opposed to embracing art historical gamesmanship. These café paintings as problematic as they might be were part of an urge to create something monumental from mass experience which finally bore fruit when he completed Bar at the Folies Bergere in the year before his death. Manet’s Waitress is the picture I have stood in front of for the greatest amount of time since first encountering it in 1983. It isn’t a masterpiece but only a master could have painted it.

What was my eighteen year old self looking to find in historical painting? Epic battles, mythological scenes and togas executed with exquisite technique. I had somehow accepted the notion that art from it’s primitive origins had improved over the centuries until hitting its peak during the Renaissance and then subsequently declining leaving us with ‘modern art’ something shallow, empty and full of deceit. What the National Gallery gave me were the togas and the epic tales but also the modern, the everyday, the unremarkable transformed in paint – just paint – into something marvelously affecting. The world remade. Our world remade.

Paul Brandford September 2018

POSTCARD FROM THE PAST

There was no art in my parent’s house. The feature wall of raw brick that divided the lounge from the dining area of our housing estate new build supported two vertical rows of decorative horse brass and a breastplate, again in brass, with cross swords running through it from behind. These items were devoid of genuine function beyond representing a certain kind of aspiration regarding the stabilisation of an identity. The estate was young; a blank slate in which the houses were more or less identical so what went on one’s feature wall counted for something.

By 1979 we’d been there eight years or so, the kids that populated the estate had gone through primary schools largely ended up at the same secondary and were on their way to choosing or sitting their O Levels. As much as they are now exam grades were a religion probably more for the parents than their offspring. The school wasn’t big on art, or to put it another way – art education, where were the jobs you could get, the career advantages, the respect? It wasn’t really a choice for those that couldn’t more of a hobby break for those that could, the art rooms had a distinctive atmosphere I remember a poster of Vermeer’s Milkmaid looming over us. It was never discussed but it hung there underlining our own technical inadequacies, year in – year out. In these rooms the art teachers flaunted their artiness but taught nothing.

The school’s single art trip was on offer to those taking the subject further – a visit to the Tate Gallery. My sister, the year above me at school, was first. She returned home with three or four postcards. I remember a portrait by Meredith Frampton depicting an elegantly poised young lady dressed simply standing next to a cello and a vase. In its way it was entirely artful but somehow in a state of remove like a porcelain statuette rather than a person and not so unlike the Lladro figurines my parents brought back from their Spanish resort holidays. The other postcards have gone from my recollection with the exception of one. This was the exact opposite of the Frampton this was a Lucian Freud.

At the age of fourteen I hadn’t seen an actual painting, any painting made by someone not in my school let alone a painting of a naked woman. My sister flashed the postcard as if it were nothing- just another souvenir from another trip underlining her unspoken and unassailable credentials as our family’s most sophisticated and most radical presence. Freud was known to begin his pictures starting from an eye and then to cautiously move outwards when satisfied with what he had made. Around this time many of his paintings were abandoned not so very far from these initial statements as if somehow he could not find his way, It seemed to me back then that her eye was the key to it all. Although not looking directly out it attracted and repelled at the same time as if what it was trying to say was somehow barbaric or disturbing.

Freud himself was there and not there. His brushes, his pot, his knife, his woman. Back then he was just a name on a postcard and not quite as memorable as the words Meredith Frampton, as much as he had created the picture I could tell that he had created the circumstances which made the picture possible. It was a peculiar thing, it was a personal thing. She – whoever she was – was a knot, a contorted knot of humanity with a leg oddly arcing out in a manner that defied anatomical expectation. The depiction of that leg as a simplified curve contradicting the intricate naturalism of the head and torso made the image memorable creating an unexpected hook beyond its anguished nakedness.

Some forty years later this picture is back in the forefront of my thoughts – I am now roughly the same age as Freud when he painted it. My sister, who was so good at everything back then, became not the shining star my parents thought they were nurturing not the artist that my art teachers praised in front of me but someone else. I became the artist and here I am looking at the same painting – my sister’s painting in many ways – on the walls of All Too Human back at the beginning at the Tate Gallery. Today I don’t just see it, I can see into it, with the experience of having looked at many, many Freuds and with the experience of having read so much about him from the poetic to the analytical, to the gossipy. Time changes you. You are no longer on the outside of someone else’s experience – you are on the inside of your own and something can be made of that.

Discounting the tiniest of depicted smears there is no paint in the picture, except for that which is on the picture – it is present and absent like Freud himself. He has not set his palette down to rest alongside his other tools. He might still be in the act of painting- meticulously stroking the picture. His brushes stroke the woman, stroke the bed or stroke the claustrophobic void so shutting us in with her and shutting us in with him.

His painter’s stool grows and stretches out towards her, instinctively one knows that she’s not a life model who might have say walked out of a Coldstream painting and into this one. She’s not simply a visual problem to be resolved – she’s a different sort of problem; something of a cornered animal, something of a tortured soul. His brushes, as yet unused, might caress with the coarse awkwardness of pig hair and his knife might scrape away the dissatisfaction of a false move but his pot has a presence beyond its function. One might clean a brush or thin down some paint but the pot is a character in the way that the other implements are not. (Freud’s later paintings have oceans of rags or moonscapes of paint encrusted walls offering some indication of how his physical processes transform the space within his pictures). But here we have his pot- in geometric conversation with her nipple, painted in tight swirls (much like her pubic hair) and both easily within the painter’s reach. Its interior is moist awaiting a brush to present itself.

Reality and unreality are at the centre of this image’s disquiet. The curving leg, the fist tightly trapped between torso and thigh, the taught forearm ending in fingers to almost become a paintbrush made flesh – as static as it is it suggests squirm, suggests discomfort, suggests Francis Bacon. She is pinned down in this sparse but theatrical space, the representation of her is both controlled and controlling – relentlessly so. The only flash of wit is found near the bottom corner as the bedspread’s tassels become an extra set of toes casually twisting around themselves and sweeps of drapery become imagined brushstrokes made by the painter’s resting utensils.

In 1978 Lucian Freud was nothing to me, his image a surprising intrusion into our turgid domesticity. In 2018 although a long way from being my favourite painting, or even my favourite painting of his this is the one thing that opened a door onto another world – a door which I chose to walk through.

Paul Brandford August 2018

YOU ARE HERE

There is far too much to look at. Too much online content, too much reality, too much mainstream media coverage. Chances are that we could easily spend most of the rest of our lives casually glancing, scrolling, liking or muting. We will have precious little time for looking or even seeing let alone reflecting upon whatever our reactions were to our experience. It comes as little surprise to me that artworks struggle for this diminished attention.

Artists either by choice or by chance have developed strategies to counter this dilemma. Paintings and drawings quite recently seem to have become less troublesome, less irritating, less demanding and more pleasingly likeable and over eager to entertain. You might ask yourself what an artwork is actually representing, what it might be about. You might ask yourself this before attempting to read the label or before getting lost in some convoluted essay about what the artist claims to be exploring through this work. Art when created or purchased as a fashion accessory or a branding exercise becomes swallowed by that context. Works knowingly following the money provide surface not depth, simplicity rather than contradiction, sterility rather than exuberance.

Seventy years ago artists working in the aftermath of the Second World War and the shadow of the Cold War were associated with an existential imperative which to the artists chosen for this exhibition appears to be a common interest– an acknowledgement that the artwork whilst being made hangs in the balance and might end in failure or even destruction. This attitude seeped into their working arrangements, risk taking, living upon one’s instincts and the cycles of making and remaking through which a work might emerge as if purely by chance. These quirky hand made things created to their own requirements are intrinsically human, intrinsically humane.

Today we find ourselves in the midst of great uncertainty. What can now be taken as given; the value of culture, the ability of our politicians, the health of our economy, the defeat of our enemies? On our screens we view the movement of people, the uprooted, the oppressed and the opportunistic. If it can happen to them might it not one day happen to us? We see attack after attack on innocent civilians the world over. This very real sense of unease pervades our daily lives You Are Here is not an escape but a reflection.

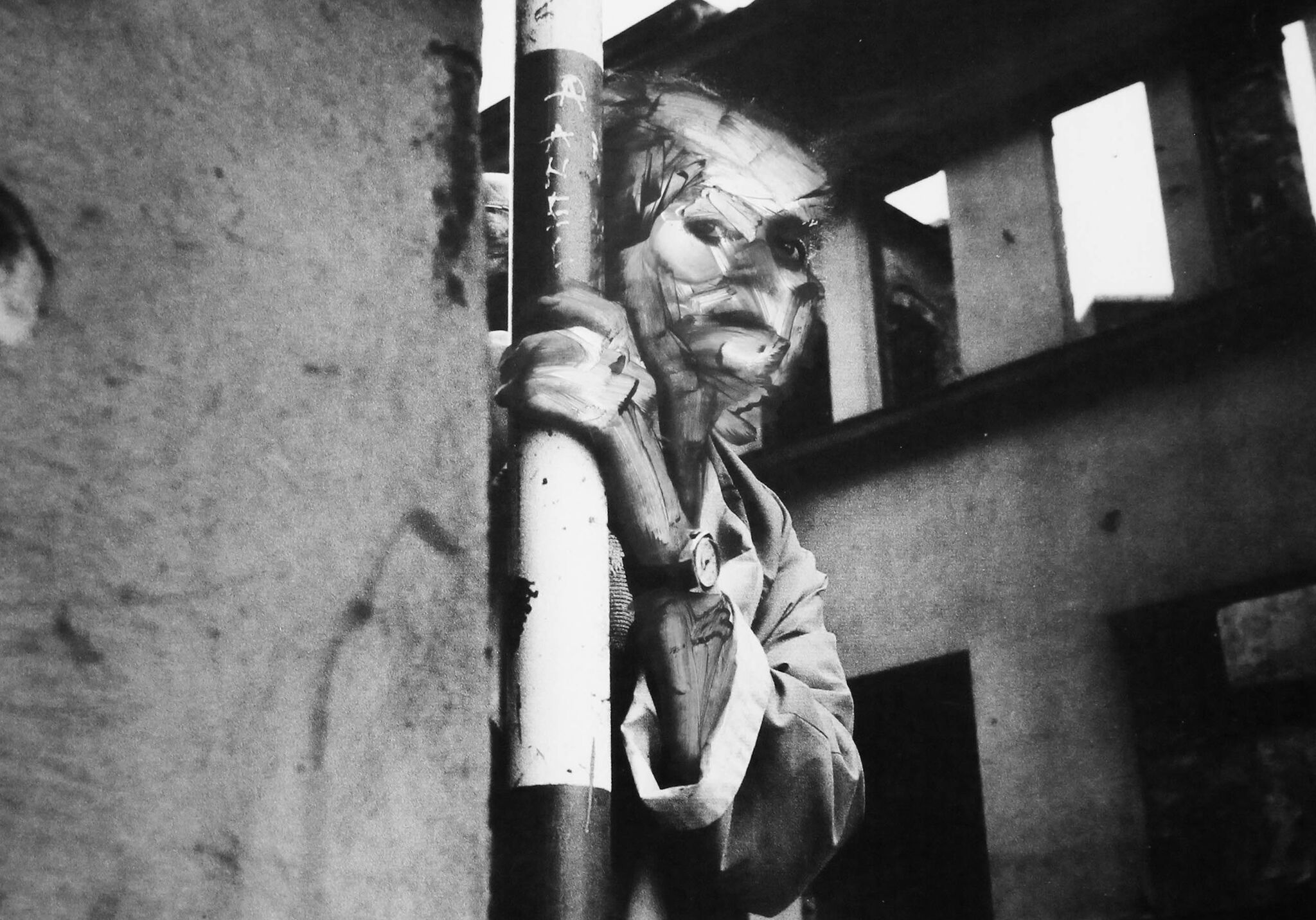

The majority of artists within this exhibition do not directly describe or even refer to political events but within their work in general one might detect that same dark thread of anxiety which runs through what can be seen in the world today. This is primarily an exhibition about people. These people might never have been real – summoned, instead, from an imagined past or contorted into being from a range of internet sources, others may have begun life as printed material found by chance alone. In the studio faces are filtered, corrupted, misquoted and modified. Subjects haven’t sat for hours awaiting an acceptable likeness. What they all might have in common is that they arrived through a marriage of technology and tradition, seriousness and absurdity, technique and cackhandedness.

The artists themselves come from roughly the same generation most attending art schools in the late eighties and early nineties, sharing not only a similar set of cultural references but a certain kind of art school background where an understanding of context and process were important but an artwork’s existence as a physical and visual entity was never secondary to its function as an intellectual trigger. Collectively the works call for some kind of instinctive reaction, surfaces are there to be scratched beneath, uncomfortable truths are inadequately glossed over, masks allowed to slip. The public persona and the private self are at war with one another. Clues pieced together will not necessarily reveal an answer but might deepen the question. Something fleeting, something fugitive somehow arrested just prior to its escape or disintegration. Images unearthed, discovered, images on the cusp of being wiped out, wiped away. Time is always present on both sides of the picture. In the studio where the imagination transforms years of practice, years of wandering up blind alleys and barking up wrong trees.

This time is as invisible to you as the studio itself. The passage of time is also frozen within the image. Like fruit a picture germinates, matures and then rots; layer upon layer – additions and subtractions, comings and goings, collisions and near misses, changes of direction.The artist trusting in some kind of obscure understanding knows when enough is enough and stands back leaving some kind of meaning hanging there within the image– suspended just, but only just, out of reach. These artworks attempt to speak of our time and of our predicament. Why they were made in the way that they were but they might somehow hint at what we have become and what, if anything, might lie ahead.

Paul Brandford January 2018

List of illustrations

Jeanette Barnes – Shibuya Crossing, Tokyo 2017 168 x 232 cm

Paul Brandford – Different Bottle Same Piss 2017 244 x 366 cm

Broughton and Birnie – Swamp Life 2016 152 x 232cm

Tom Walker – The Night I Should Have Stopped 2016 85 x 118 cm

Charlotte Steel – Circle of Lust 2016/17 71 x 73 cm

Corinna Spencer – Lady Drawing 2017 21 x 15 cm

Vanessa Mitter – Unquiet Brides 2015 150 x 120 cm